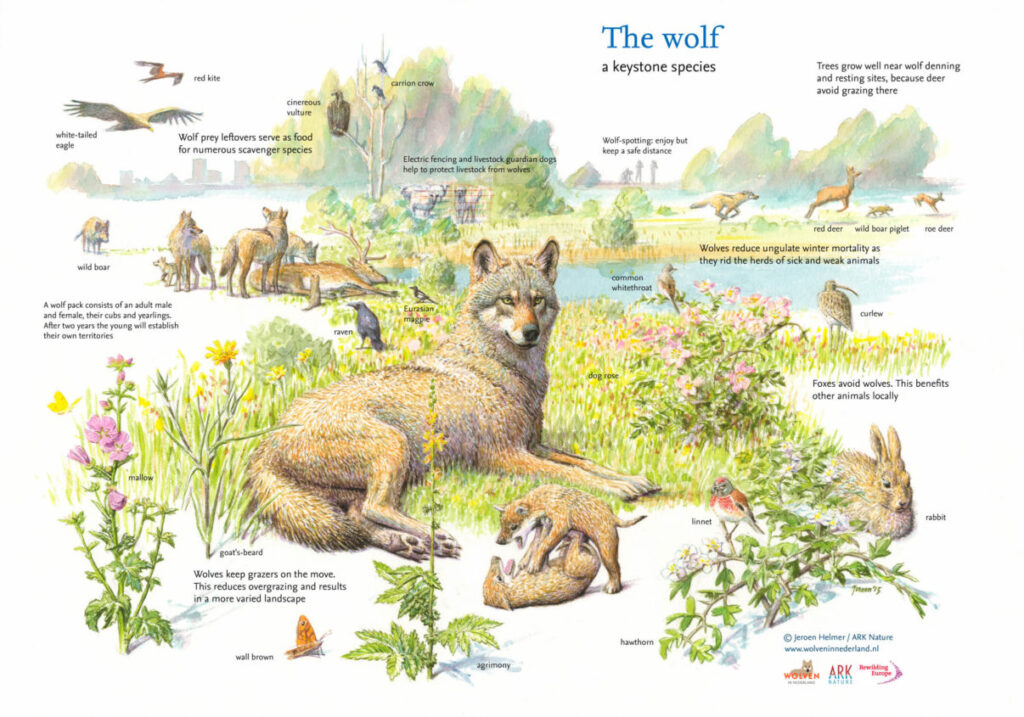

In the circle of life every species plays a role. The wolf in our landscapes is as important as herbivores, plants and other links of the food chains.

The wolf as a big predator helps to balance the herbivores’ populations, eliminates weak and sick animals, and prevents their populations from excessive growth. This has a positive impact on the landscape, enabling many other plants and animals to flourish. In this regard, wolves initiate a domino effect, affecting species as diverse as birds, fish, mammals, and insects. Without the presence of predators such as wolves, ecosystems are less healthy and support less abundant wild nature.

When wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park in the western United States in 1995 after a 70-year absence, their comeback ignited a chain reaction, boosting the restoration of ecosystems that had been degraded in their absence. The wolves balanced and keep on the move the elk population. They stopped to intensely browse the willow, so the willow stands along streams became stronger. That caused the comeback of beavers, which, in their turn provided space for many birds, fish, insects, and other species.

There are five subspecies of wolf found in Europe, of which the Eurasian wolf is the most common and widespread. On average it weighs around 40 kg, with relatively short and coarse tawny fur. Wolves are very smart and highly social animals that live in extended family groups called packs. Adaptable and resilient, they can survive in a variety of habitats, including forests, tundra, mountains, swamps, and deserts.

A long history of hunting and persecution meant that by the first half of the twentieth century the animal had disappeared from most Western European countries. Later on, the opinion on wolves began to change, and the animal is now protected in most European countries and is gradually coming back to our landscapes.

In many areas of Europe wolves will prey on livestock, which causes farmers and shepherds to resent the animal’s presence and in many cases shoot the animal on sight. However, this predation is largely due to a scarcity of the wolves’ natural prey. Studies have shown that even when livestock is abundant in wolf territory, wolves still mostly prefer to feed on wild animals such as deer and wild boar. Boosting the availability of natural prey is therefore critical to improving human-wolf relations. It is also important to include local stakeholders in management plans, establish suitable compensation schemes and work on coexistence measures together.

In the Rhodope Mountains, Velebit Mountains and Greater Côa Valley local rewilding teams are supporting natural wolf comeback by boosting the availability of natural prey (red deer, fallow deer and roe deer), raising awareness and implementing a livestock guard dog programme.

In the Danube Delta wolf can help to regulate the golden jackal population that is already arguably causing problems according to the local communities. Wolf occurs in the delta and Tarutino steppe, but is still very rare. Hunting pressure and the severe decline of natural prey are the main barriers for wolves in the area. Restoring the delta fauna and roe deer populations in the first place would help to re-establish wolf, and minimize conflicts with farmers and jackal populations at bay.